Journal of Reliable and Secure Computing

ISSN: pending (Online)

Email: [email protected]

Network terminal devices such as smartphones and electric vehicles are becoming increasingly pervasive and intelligent. Equipped with powerful sensing and computing capabilities, these devices generate and consume massive amounts of data, which form the foundation for diverse intelligent applications. With the rise of mobile edge computing, machine learning and deep learning are deployed at the network edge to support data-driven services and real-time analytics [1, 2]. This paradigm enables efficient model training close to data sources, but also raises new concerns. Traditional centralized machine learning approaches require aggregating raw data on a central server, which introduces substantial risks of privacy breaches. Federated learning (FL) addresses this issue by coordinating local training across distributed participants without exposing raw data. By preserving privacy and reducing network transmission requirements, FL has become an important framework for collaborative model training in edge environments.

Meanwhile, the rapid growth of the Internet has intensified cybersecurity threats. Traditional intrusion detection techniques, whether feature-based or anomaly-based, struggle to cope with the sophistication of modern attacks. Machine learning and deep learning have significantly improved the performance of intrusion detection systems (IDS) [3]. However, in large-scale and multi-party environments, data privacy concerns often discourage participants from sharing sensitive information, despite the demand for diverse datasets to build accurate detection models [4]. Although FL enables privacy-preserving collaboration, federated IDS still face fundamental challenges in building trust among participants, ensuring the integrity of shared updates, and scaling across heterogeneous devices and networks.

Blockchain technology offers a complementary foundation for addressing these challenges. As a decentralized and immutable ledger[5, 6, 7], blockchain supports secure model aggregation, transparent data exchange, and auditable participant behaviors. By mitigating single points of failure and enabling verifiable collaboration, blockchain enhances both the trustworthiness and robustness of federated IDS. Recent studies in multiple domains demonstrate that the combination of FL and blockchain strengthens privacy protection, provides scalable trust management, and supports the construction of more reliable IDS. Building on these observations, this paper presents a taxonomy of research in this area, analyzes open challenges, and outlines perspectives for advancing privacy and trust in blockchain-federated IDS.

Research on IDS has evolved across multiple dimensions. The work in [8] presents a broad survey covering application domains, preprocessing techniques, attack detection methods, evaluation metrics, author collaborations, and datasets, offering a detailed landscape of IDS research. Similarly, [9] introduces fundamental IDS concepts and common detection techniques, comparing machine learning- and deep learning-based methods as well as their associated training datasets. Feature engineering for anomaly detection is emphasized in [10], which categorizes IDS according to machine learning, deep learning, and swarm or evolutionary algorithms, and discusses datasets and performance assessment methodologies.

More recent studies shift toward distributed and collaborative approaches. In [11], FL is applied to anomaly detection in IDS, with discussions of privacy protection alongside challenges such as latency, misjudgment, and poisoning attacks. The work in [12] categorizes IoT IDS security issues using a two-tier taxonomy, proposing an integrated platform that combines explainable AI, FL, and social psychology. Likewise, [13] investigates data security and privacy in IoT environments, highlighting blockchain's potential to enhance trust and integrity in machine learning-based IDS. The joint use of FL and blockchain is explicitly analyzed in [14], identifying how the two technologies complement each other in preserving privacy and enabling secure collaboration. Complementary to this, [15] reviews historical privacy and security challenges in IoT and categorizes research efforts applying blockchain and machine learning to safeguard IDS.

A comparative overview of these studies is provided in Table 1. While these surveys contribute valuable insights into IDS, FL, and blockchain, most remain fragmented, addressing isolated aspects without a unified perspective. In particular, systematic analysis of privacy and trust issues in blockchain-federated IDS is still lacking, and no comprehensive taxonomy currently exists. This gap motivates the present work, which consolidates prior contributions and provides a structured view of challenges and perspectives.

| Research | Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| [16] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [9] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [8] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [17] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [10] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [11] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [18] | 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [19] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [12] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [13] | 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [14] | 2023 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [15] | 2020 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [20] | 2020 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [21] | 2022 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [22] | 2020 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [23] | 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [24] | 2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This survey | — |

The key contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

We provide a systematic survey of IDS that incorporate FL and blockchain. Their architectures, security objectives, and application scenarios are analyzed, highlighting both strengths and limitations.

We identify and categorize the main threats faced by FL-based IDS, including data-related, communication-related, and model-related threats. Corresponding defense mechanisms are summarized and mapped into a taxonomy, offering a structured perspective of the research landscape.

We review representative studies of IDS integrating FL and blockchain across multiple domains, including vehicular networks, industrial IoT, medical IoT, and metaverse environments. A comparative synthesis is presented to clarify their design choices and research focuses.

We discuss the key challenges of deploying blockchain-enhanced FL-based IDS, such as communication efficiency, non-IID data distribution, limited IoT device performance, incentive mechanisms, and system security. For each, we outline potential research directions and highlight open issues.

Based on the above analysis, we provide perspectives on future opportunities for developing secure, scalable, and privacy-preserving IDS that combine the strengths of FL and blockchain.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the background of IDS, FL, and blockchain, and summarizes representative studies in each area. Section 3 analyzes privacy and trust issues in federated IDS, proposes a taxonomy of threats and defenses, and reviews representative studies across domains. Section 4 discusses key challenges of blockchain-federated IDS, including communication efficiency, non-IID data distribution, deployment on resource-constrained IoT devices, incentive mechanisms, and system security, and outlines potential future directions. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by highlighting the main findings and prospects for secure and privacy-preserving IDS.

IDS, blockchain, and FL are three fundamental research areas underlying this study. IDS provide the application context, while blockchain and FL offer the enabling technologies for addressing data privacy and trust issues. This section reviews their key concepts, taxonomies, and representative methods. Specifically, Section 2.1 introduces IDS and the evolution from traditional approaches to ML/DL-based methods. Section 2.2 summarizes the foundations of blockchain, including its components, taxonomy, and consensus protocols. Section 2.3 presents FL, highlighting its categories, training process, and representative algorithms. Together, these overviews lay the groundwork for analyzing data privacy and credibility threats, as well as the integration of FL and blockchain into IDS, which will be discussed in Section 3.

As the Internet evolves and the number of connected devices continues to grow, cyberattacks targeting heterogeneous devices and users have become increasingly complex and diverse. IDS are designed to monitor and analyze activities in networks or hosts, identify potential malicious behaviors, and trigger alerts or interventions. Research on IDS has been active for decades, and this subsection provides an overview of their taxonomy, detection mechanisms, and the advances brought by machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL).

IDS can be classified from multiple technical perspectives. Based on the operating environment, IDS are divided into Host Intrusion Detection Systems (HIDS) and Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS)[10]. Based on the detection mechanism, IDS are typically categorized into signature-based detection and anomaly-based detection.

Host Intrusion Detection Systems (HIDS): HIDS operate directly on individual hosts or terminals [25, 26]. By monitoring system activities and comparing them against known policies, rules, or patterns, HIDS can detect malware [27], unauthorized access, or unusual file modifications. Although event logging and tamper-proof mechanisms enhance reliability, HIDS suffers from drawbacks such as high resource consumption and performance degradation, limiting its scalability.

Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS): NIDS monitor network traffic at strategic points in a network [28, 29]. By analyzing subnet traffic and comparing it against anomaly or signature libraries, NIDS can detect intrusions, malicious scans, and unauthorized access attempts. This centralized visibility improves early detection and response. However, with the rapid growth of network traffic volume, per-packet inspection becomes computationally expensive, and subtle or novel attacks may escape detection. Consequently, most current IDS research focuses on NIDS, and unless otherwise specified, IDS is commonly used to denote NIDS.

Signature-Based Detection: Signature-based IDS rely on known attack patterns stored in signature libraries [30, 31]. When traffic matches a predefined signature, the system raises an alert. This method is highly effective against previously identified attacks but cannot detect novel or obfuscated variants.

Anomaly-Based Detection: Anomaly-based IDS build statistical or ML models of "normal" behavior and flag significant deviations as potential intrusions [32, 33]. While capable of detecting zero-day or unknown attacks, anomaly-based systems often suffer from high false positive rates, as normal variations may be misclassified as anomalies.

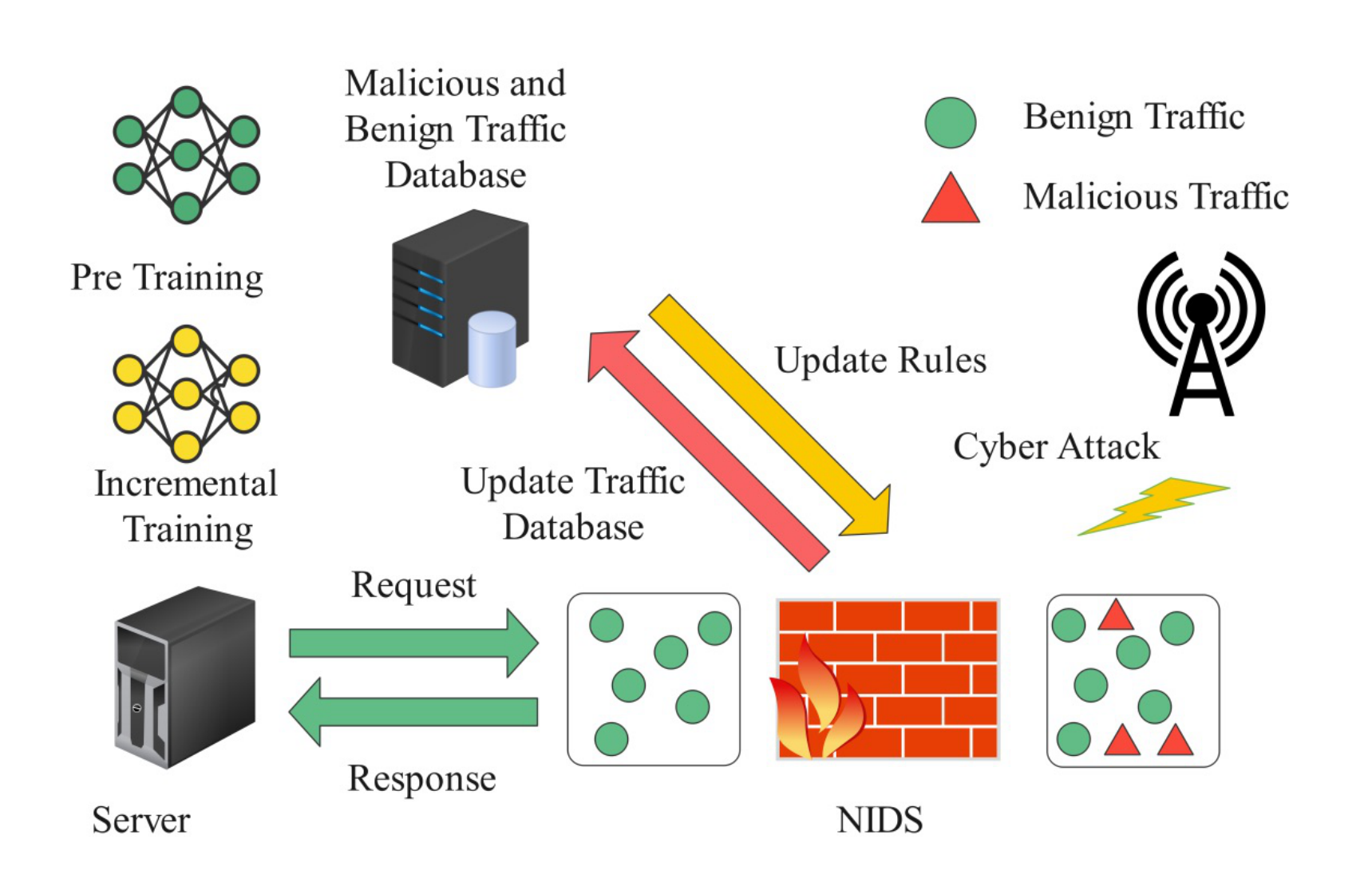

Recent years have witnessed a paradigm shift toward incorporating ML and DL into NIDS. These approaches enable IDS to automatically learn traffic representations, distinguish benign and malicious flows, and adapt to evolving attack behaviors. Typically, a labeled dataset is used to train an initial detection model, which then classifies new traffic and incrementally updates itself based on inspection results. The general workflow of ML-based NIDS is shown in Figure 1.

Numerous algorithms have been investigated. For instance, an ANN-based IDS evaluated on the NSL-KDD dataset achieved detection and classification accuracies of 81.2% and 79.9%, respectively, using Levenberg–Marquardt and BFGS training methods [34]. Other studies employed ensemble learning methods such as random forest, gradient boosting, AdaBoost, and SVM to detect wireless network attacks [35]. Semi-supervised approaches have also been explored, such as a fuzziness-based method that achieved 84.54% and 71.29% accuracy on the KDDTest+ and KDDTest-21 datasets, respectively [36]. Deep learning techniques, including Gaussian–Bernoulli restricted Boltzmann machines [37], demonstrated superior performance in denial-of-service detection compared to traditional ML classifiers. In addition, LSTM-based methods tailored for in-vehicle networks (IoVs) achieved over 90% accuracy while preserving message confidentiality [38]. Hybrid approaches combining fuzzy rough sets, GANs, and CNNs further enhanced IDS efficiency by achieving low-latency and high-speed detection [39].

These advances confirm that ML/DL-based IDS outperform traditional rule-based methods, especially in dynamic and large-scale network environments. However, they also highlight the increasing dependency on large volumes of distributed data, thereby motivating the need for FL and blockchain solutions, which are further discussed in later sections.

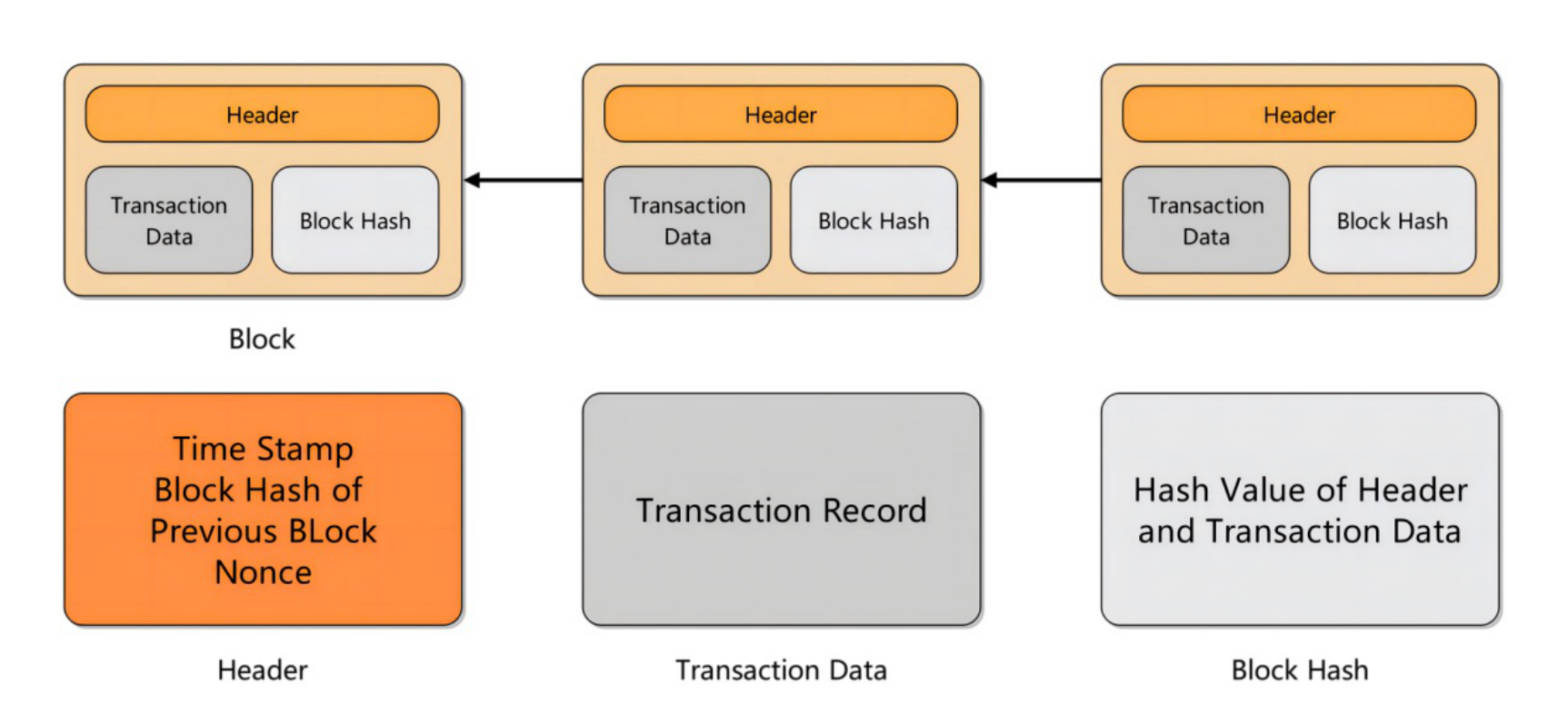

Blockchain is a decentralized and tamper-resistant public ledger maintained over peer-to-peer networks. It enables multiple participants to securely record, verify, and share transaction data without centralized control. Each node, including those deployed at the edge or on Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) servers, participates equally in validating transactions under a consensus mechanism [24]. In this subsection, we summarize blockchain's key components, taxonomy, and consensus mechanisms, with emphasis on how these features contribute to data security and trust in distributed IDS.

A blockchain consists of a sequence of linked blocks, each containing a block header and a transaction list, as shown in Figure 2. The header includes metadata such as timestamps and the previous block's hash, while the data list stores transaction information [40]. Blocks are connected by cryptographic hash functions (e.g., SHA-256), ensuring that any modification in historical data invalidates subsequent blocks. The distributed network of nodes maintains a complete copy of the ledger, exchanging updates through secure communication protocols. These properties—immutability, transparency, and distributed maintenance—form the foundation for blockchain's application in enhancing IDS trust and accountability [41].

Blockchain networks can be categorized into public, private, and consortium blockchains [42].

Public blockchains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, are open to all participants. Bitcoin ensures transparency and immutability via Proof of Work consensus [43], while Ethereum extends blockchain's functionality through smart contracts on the Ethereum Virtual Machine, enabling decentralized applications [44].

Private blockchains restrict membership to authenticated participants, offering higher throughput at the cost of decentralization [45].

Consortium blockchains are governed collectively by a group of organizations. Examples include Corda and Hyperledger Fabric, which emphasize modularity, access control, and customizable consensus protocols [46, 47]. Consortium blockchains balance decentralization with organizational control, making them attractive for privacy-sensitive applications such as collaborative IDS.

Table 2 summarizes features of representative blockchain platforms, illustrating the diversity of deployment scenarios.

| Blockchain Platform | Primary Scene | Feature | ||

| Bitcoin | Digital Currency |

|

||

| Ethereum | Smart Contracts, Decentralized Applications |

|

||

| Hyperledger Sawtooth | Digital Identity Verification |

|

||

| Hyperledger Fabric | Enterprise Applications |

|

||

| Stellar | Financial Service |

|

||

| EOS | Decentralized Application |

|

||

| Algorand | Smart Contract |

|

||

| Polkadot | Cross-Chain Transaction |

|

Consensus protocols ensure agreement among distributed nodes on the validity of transactions. Two main design philosophies exist: proof-based protocols, which grant block generation rights probabilistically (e.g., PoW[43], PoS), and committee-based protocols, which achieve consensus via voting among authorized participants [48, 49]. Hybrid mechanisms such as PBFT, DPoS, and PoSpace combine these approaches for different performance and trust trade-offs. Table 3 presents typical consensus algorithms and their applications.

Smart contracts further extend blockchain by embedding programmable scripts that automatically execute when predefined conditions are met [50]. They provide transparency, auditability, and automation, enabling the design of self-enforcing policies for secure data exchange.

In summary, blockchain's decentralization, immutability, and programmable trust make it a promising technology for enhancing data credibility, participant accountability, and secure collaboration in federated IDS, which we discuss in later sections.

| Consensus Protocol | Application Example | Features | ||

| Proof of Work, PoW | Bitcoin |

|

||

| Proof of Stake, PoS | Ethereum |

|

||

| Delegated Proof of Stake, DPoS | EOS |

|

||

| Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance, PBFT | Hyperledger |

|

||

| Proof of Space, PoSpace | Filecoin |

|

||

| Proof of Burn, PoB | Slimcoin |

|

Federated learning, first introduced in [51], has emerged as a promising paradigm for privacy-preserving collaborative training. Traditional centralized machine learning requires collecting all raw data on a central server, which raises significant privacy and security concerns. In contrast, FL distributes model training to edge devices, where participants perform local training on their data and only share model updates with a central aggregator [52]. This avoids direct transmission of sensitive information and substantially reduces the risk of privacy leakage.

Depending on the distribution of data across participants, FL can be classified into horizontal, vertical, and federated transfer learning[53]. Horizontal FL applies when participants share similar feature spaces but have different sample spaces, enabling cross-device training while improving model generalization. Vertical FL applies when participants share the same sample space but with different feature spaces, enabling cross-silo collaboration (e.g., different organizations holding complementary attributes of the same users). Federated transfer learning addresses scenarios where both feature and sample spaces differ, transferring knowledge from a source to a target domain while maintaining privacy.

This taxonomy highlights the flexibility of FL for diverse data distributions in large-scale, heterogeneous environments such as IoT and edge networks.

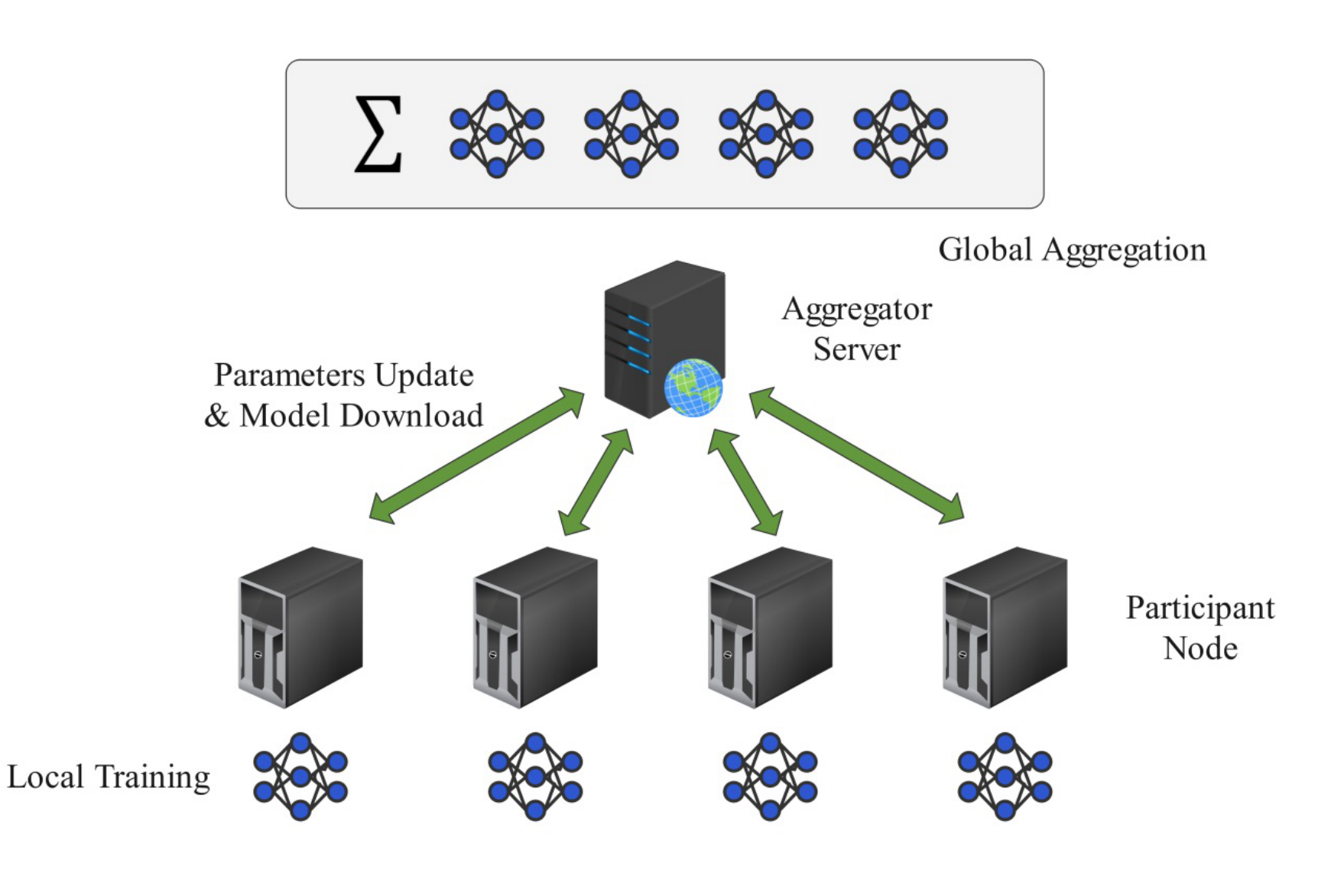

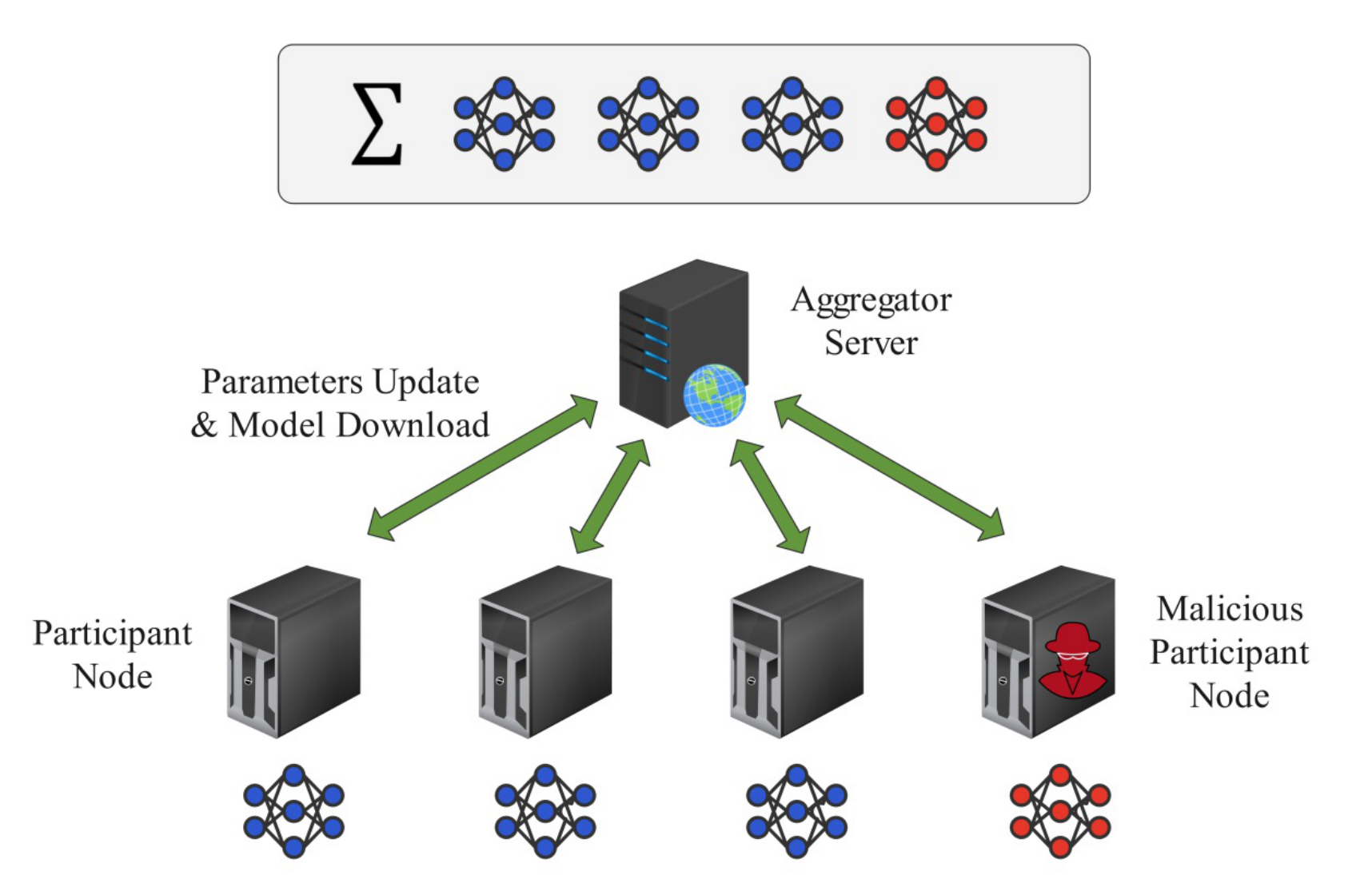

As illustrated in Figure 3, a typical FL process involves four iterative stages: (i) model distribution, (ii) local training, (iii) parameter update, and (iv) global aggregation. At the start of each round, a central server distributes the global model to selected participants. Each participant performs local training on its private data and uploads parameter updates or gradients. The server aggregates these updates—commonly using weighted averaging—to obtain a new global model, which is redistributed for the next iteration. This iterative process allows the global model to progressively capture knowledge from distributed data sources, while raw data remains local throughout the entire training.

Representative aggregation and privacy-preserving techniques include: Federated Averaging (FedAvg): The canonical algorithm where local updates are averaged by the server to update the global model [54]. Federated Reverse Gradient: Instead of transmitting parameters, participants upload reverse gradients, which are aggregated by the server to update the global model. Secure Multi-Party Computation (MPC): Participants encrypt model updates and only share computation results, enabling secure aggregation without exposing individual updates [55].

These approaches vary in computational overhead, communication efficiency, and resilience against inference attacks. Hybrid mechanisms combining secure aggregation, differential privacy, or homomorphic encryption are increasingly adopted to balance privacy with model utility.

In summary, FL enables collaborative learning while preserving privacy, making it a natural fit for intrusion detection in edge networks. However, practical deployment faces challenges such as non-IID data, high communication costs, and trust among participants. These issues are analyzed in detail in Section 3.

This section analyzes the scenarios where IDS face data privacy and credibility threats and reviews the latest research. We focus on privacy-preserving NIDS by examining user data protection and system performance in the context of FL. Furthermore, we discuss the limitations of federated learning–based NIDS and highlight how blockchain integration can provide more secure, trustworthy, and scalable solutions.

Predicting and preventing malicious traffic is the primary purpose of Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS). Machine learning- and deep learning-based IDS heavily depend on large-scale datasets to differentiate benign and malicious traffic. Traditionally, centralized IDS are trained on aggregated datasets and then deployed at endpoints. However, with the rapid growth of IoT and edge computing, data are increasingly generated and stored at distributed nodes. Centralized IDS suffer from scalability issues in model training, malicious behavior detection, and data transmission. Moreover, heterogeneity among devices leads to severe data imbalance, resulting in classification bias, poor generalization, and reduced detection performance. To address these issues, techniques such as re-sampling, synthetic data generation, collaborative learning, and ensemble methods have been applied in distributed IDS [56, 57, 58]. Table 4 summarizes widely used IDS datasets (e.g., KDD99, NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, CICIDS2017, CSE-CIC-IDS2018), which continue to serve as benchmarks for evaluating both detection performance and privacy-related risks in IDS research.

| Dataset | Year | Attacks | Features | ||

| KDD99 | 1999 | DoS, Probe, R2L, U2R |

|

||

| NSL-KDD | 2009 | DoS, Probe, R2L, U2R |

|

||

| UNSW-NB15 | 2015 | DoS, Backdoor, Fuzzers, Worms, Reconnaissance, etc. |

|

||

| CICIDS2017 | 2017 | DoS, Web Attack, Infiltration, Botnet, etc. |

|

||

| CSE-CIC-IDS2018 | 2018 | DoS, DDoS, Scanning, Malware, Web Attack, Phishing, Botnet, etc. |

|

Beyond imbalance, data privacy and security remain critical concerns. Multi-party data collection and centralized training risk exposing sensitive participant information. Direct aggregation of raw traffic data may violate user privacy and introduce security vulnerabilities, while transmission of unencrypted data creates additional risks of theft and tampering. Studies have shown that IoT traffic often leaks privacy-sensitive information about users, devices, and platforms [59]. Static analysis tools have further revealed that many IoT applications expose sensitive flows during runtime [60]. These risks reduce participants' willingness to contribute data and undermine the credibility of collaborative IDS.

From a classification perspective, sensitive data in distributed IDS can be divided into three categories [61, 62]: (i) input data, such as traffic traces, IP addresses, and user identifiers, which may directly reveal private information; (ii) built-in data, including attack signatures, anomaly profiles, and detection models, which attackers can exploit if exposed; and (iii) generated data, such as detection results, timestamps, and alerts, which may disclose user identities or system behavior when shared across IDS nodes.

During communication, IDS data are particularly vulnerable to man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. As illustrated in Figure 4, attackers may intercept or alter traffic without detection, leveraging techniques such as ARP spoofing, DNS spoofing, and SSL hijacking [63]. Such attacks compromise both privacy and trust in distributed detection systems.

.png)

Recent studies have proposed various strategies to mitigate these privacy and credibility threats in collaborative intrusion detection. For example, evolutionary game–based incentive mechanisms encourage cooperation among participants while applying pseudonymity to conceal identities during exchanges, thereby reducing exposure of sensitive information [64]. Sparse Autoencoders (SAE) have been employed to encode raw traffic into low-dimensional representations, minimizing privacy risks while preserving useful features for intrusion detection [65, 66]. Other works integrate feature selection algorithms such as the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) with perturbation methods like the Least Squares Method (LSM) to distort sensitive attributes, protecting participants' private data without severely impacting model accuracy [67]. These solutions illustrate promising directions but are often designed in isolation, leaving open questions regarding scalability, robustness, and holistic integration in real-world IDS deployments.

To better summarize the relationship between identified threats and corresponding defenses in distributed and federated NIDS, we present a consolidated mapping in Table 5. This table categorizes threats into data-related, communication-related, and model-related issues, and highlights representative studies along with their mitigation strategies. By systematically aligning threats with defense mechanisms, this mapping provides a clearer view of the research landscape and motivates the need for more integrated solutions, which we further explore in the subsequent subsections.

| Threat Category | Typical Issues | Representative Studies | Defense Mechanisms | ||||

| Data related threats |

|

[56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62] | |||||

| Communication related threats |

|

[63] |

|

||||

| Model related threats |

|

[56, 57, 58] |

|

In traditional IDS trained on centralized data, data protection relies mainly on encryption and obfuscation. However, transmitting raw data during communication not only increases energy overhead but also poses privacy risks, especially in large-scale distributed environments where participants differ in data structures and operating conditions. FL addresses these challenges by allowing participants to keep their data locally while only sharing model parameters with a central server. This decentralized paradigm reduces the risk of sensitive data leakage and provides stronger privacy guarantees, thereby encouraging broader participation in collaborative intrusion detection.

A typical FL-based IDS workflow involves distributing a global model from a central server, training it locally on participant devices, and then transmitting updated parameters back for aggregation. For example, [68] developed an IoT intrusion detection scheme where participants locally trained a deep learning model and uploaded updates, which were then aggregated using federated averaging (FedAvg). This represents the standard application of FL in IDS scenarios.

Different detection architectures have been deployed under FL-based IDS frameworks. In [69], a CNN-GRU hybrid model was adopted, combining convolutional layers, gated recurrent units, and fully connected layers, trained locally and aggregated globally. In [70], an improved Simple Recurrent Unit (SRU) was introduced to reduce computational cost and mitigate gradient vanishing, demonstrating applicability in Industrial Control System (ICS) networks. Beyond IoT and ICS, FL-based IDS solutions have been extended to diverse domains: a two-stage leakage detection scheme in vehicular CPS (VCPS) [71], adaptive FL algorithms in satellite–terrestrial integrated networks (STIN) [72], FedBatch aggregation in maritime transportation systems [73], and DEW-Cloud-based intrusion detection in medical IoT [74]. These studies highlight the versatility of FL in protecting sensitive data across heterogeneous environments.

Overall, IDS built on FL significantly increase the difficulty for attackers to access raw data. Data owners maintain greater control and ownership, deciding when and how to share updates. Since only parameters are exchanged, FL enables cooperative learning under strict data regulations, while avoiding direct exposure of private datasets. However, limitations remain: model updates may still leak information through inference, aggregation servers may pose single points of failure, and communication overhead can be non-trivial in large-scale deployments. Table 6 summarizes the advantages and limitations of FL-based IDS.

| Advantages | Limitations | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

Research [75, 76, 77] has shown that gradient information may leak sensitive local data, making FL face both credibility and privacy risks. A major challenge is that participants must trust a central server for model aggregation. Even under a semi-trusted assumption, the server may act honestly but remain curious, attempting to infer private information from updates. To mitigate such risks, several privacy-preserving techniques have been explored.

Differential Privacy (DP). DP [78] introduces statistical noise into training data or model updates, reducing the risk of private information extraction. In FL, participants train locally and add Gaussian or Laplace noise before uploading parameters, thereby protecting privacy while retaining model utility. Work in [79] evaluated the impact of DP on intrusion detection in IoT systems, showing that aggregation functions such as Fed+ can preserve model accuracy within acceptable ranges despite the added noise.

Homomorphic Encryption (HE). HE [80] enables secure computation over encrypted data without requiring decryption. In [81], the Privacy-Enhanced Federated Learning (PEFL) framework employed linear homomorphic encryption, where participants add noise to local gradients before transmission. Similarly, [82] combined -DP with Paillier homomorphic encryption to secure parameter updates in fog computing scenarios, preventing even honest-but-curious servers from learning sensitive information.

Secure Transmission Protocols. During communication, model updates remain vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks. To address this, [69] designed a secure protocol based on Paillier HE, supporting key generation, encryption, aggregation, and decryption. Likewise, [83] applied secure key exchange protocols in an intelligent factory setting, employing RING-LWE shared keys with AES ciphers to protect communication channels against tampering.

Table 7 summarizes representative approaches for privacy-preserving federated learning, classified by the stage at which data are protected (in storage vs. in transmission).

| Paper | Data Status | Approaches |

| [79] | In Storage | Noise addition using Gaussian and Laplace mechanisms; evaluation of Fed+ as an alternative aggregation function to FedAvg. |

| [81] | In Storage | Linear homomorphic encryption (LHE) applied to noisy local gradients. |

| [82] | In Storage | Combination of -DP with Paillier homomorphic encryption for local updates. |

| [69] | In Transmission | Secure communication protocol based on Paillier HE with key management. |

| [83] | In Transmission | Secure key exchange using RING-LWE keys and AES to protect training sessions. |

While cryptographic techniques enhance privacy during storage and transmission, they do not address the systemic limitations of centralized aggregation. In particular, reliance on a single aggregation server reduces system robustness and introduces a single point of failure. To overcome these drawbacks, blockchain has been integrated into FL frameworks.

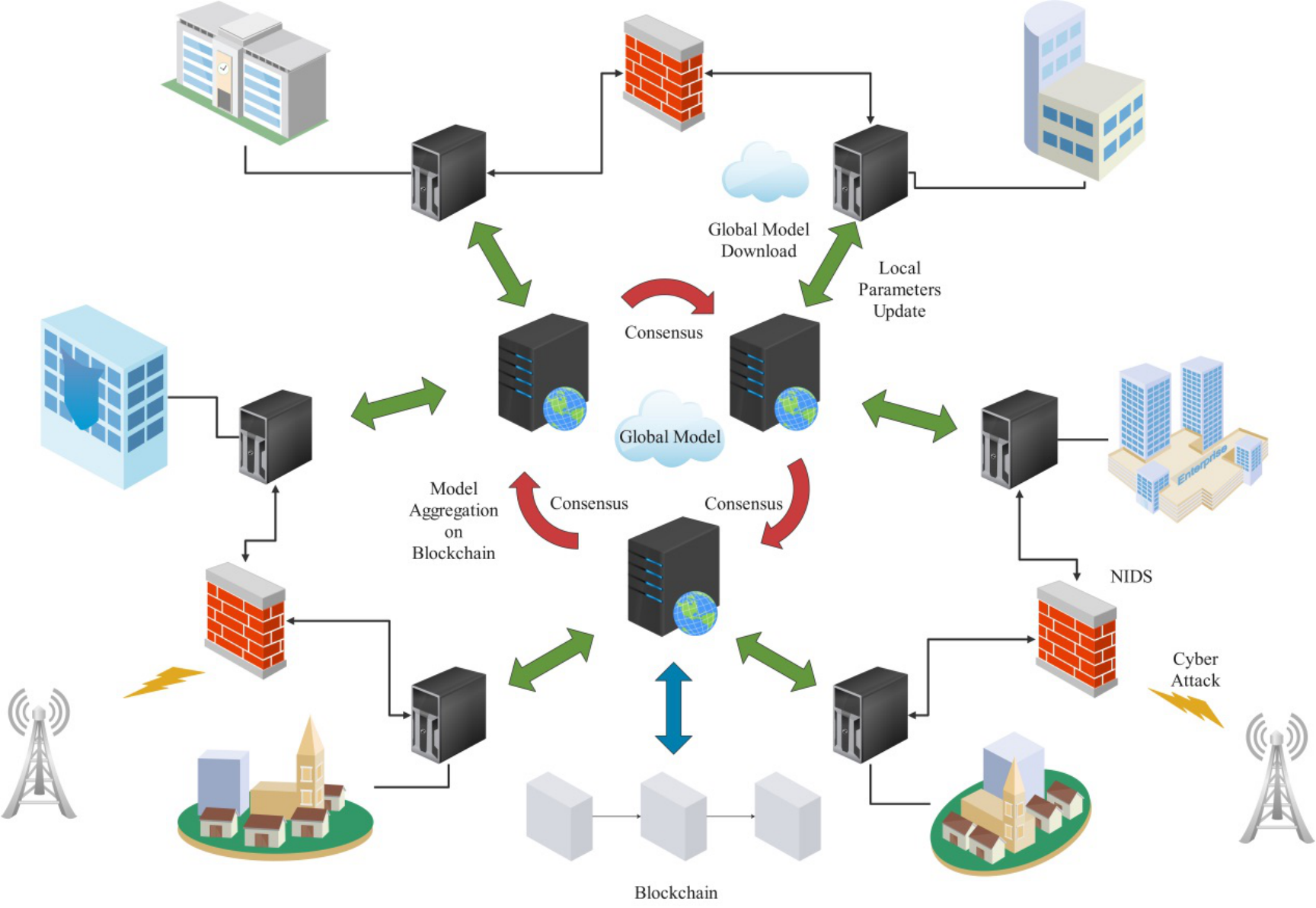

As a decentralized, immutable, and traceable ledger, blockchain supports distributed model aggregation without a central server. In blockchain-based FL, participants upload local model updates to designated miner nodes. Miners exchange, verify, and reach consensus on updates, after which a new block containing aggregated results is appended to the ledger. Participants then download the global model from the blockchain, as illustrated in Figure 5. This process not only eliminates single points of failure but also strengthens auditability and participant incentives.

.png)

Several studies demonstrate the potential of blockchain-integrated FL. BlockFL [84] incorporates blockchain miners to aggregate updates, where proof-of-work ensures validity before adding blocks containing verified gradients. In [85], blockchain stores the global model and update exchanges, using an innovative committee consensus with K-fold cross-validation to improve consensus performance. In the IoT domain, [86] developed an adaptive trust model where blockchain evaluates device credibility and miners validate local model updates before appending them to the ledger. These works collectively show that integrating blockchain with FL enhances privacy, trust, and resilience in distributed IDS.

Table 8 highlights the advantages and limitations of blockchain-integrated FL compared with traditional FL, showing both its potential to improve security and trust as well as the new challenges introduced by increased complexity.

| Advantages | Limitations | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

Building on the general integration of blockchain and FL discussed in Section 3.3, recent studies have explored concrete applications of these techniques in diverse network environments. The overall architecture of such an integrated NIDS is illustrated in Figure 6, which depicts the key interactions among edge devices, blockchain consensus mechanisms, and global model distribution for secure intrusion detection.

Vehicular Networks (V2X). IDS in vehicular networks face challenges due to the limited computational resources of vehicles and roadside units (RSUs), which act as edge nodes. Traditional federated learning-based IDS may suffer from security concerns in data storage and sharing. Research [87] proposed a blockchain-enhanced federated learning IDS where RSUs serve as mining nodes to collect, train, and aggregate model parameters from vehicles. An accuracy-proof consensus protocol ensures that RSUs providing higher-accuracy models write updates to the blockchain. A trust-based incentive mechanism further strengthens reliability, while dynamic secret sharing is used to protect uploaded gradients. On the KDDCup99 dataset, the system achieved 94% accuracy, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach.

Drone Networks. Drone devices typically operate under constrained resources, making them vulnerable to intrusion and yielding small, imbalanced datasets. To address these challenges, [88] proposed a collaborative IDS based on FL and blockchain, integrating a Conditional GAN (CGAN) and LSTM architecture. Multiple mobile edge computing (MEC) servers form a blockchain network to store global models and achieve consensus. Privacy is preserved by adding Gaussian noise to parameter transmissions. Evaluated on CIC-IDS2017, the FL-CGAN-LSTM model achieved accuracy above 99% for large classes (e.g., Normal, DDoS, PortScan) and improved small-class detection (e.g., Infiltration, Bot) from 29% to over 95% after dataset extension.

Industrial Edge of Things (IEoT). In heterogeneous industrial IoT environments, devices run under diverse systems and generate privacy-sensitive data. To secure such systems, [89] proposed Fed-Trust, a blockchain-based FL intrusion detection model employing a Time Convolutional GAN (TCGAN) for semi-supervised learning on partially labeled data. A blockchain-based reputation system records gradients and ensures credibility, while fog computing offloads mining to enhance scalability. The use of Residual Temporal Convolution (RTC) and Causal Dilated Convolution (CDC) layers enables effective modeling of multivariate time series data. Credit Contracts provide lightweight incentive and trust mechanisms, improving throughput compared to Bitcoin-like blockchains.

Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). Medical IoT environments involve highly sensitive data and demand strict privacy guarantees. To address this, [90] introduced a blockchain-based FL architecture for intrusion detection in IoMT. The framework eliminates the central server, instead using IoT gateways as participants in a federated network, while Hyperledger Fabric maintains distributed ledgers. Local updates and aggregated global models are recorded as immutable transactions, complete with timestamps for auditability. This design enhances trustworthiness and makes tampering with medical intrusion detection data significantly more difficult.

Metaverse-Oriented IDS. The metaverse relies on extensive IoT connectivity and thus inherits traditional IoT security threats. To address this, [91] proposed MetaCIDS, a collaborative IDS combining blockchain and FL. It uses an unsupervised autoencoder for zero-day attacks and a supervised classifier for known attacks, with model updates managed by blockchain using practical Byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT). Intrusion alerts are validated by smart contracts before being broadcast as global alerts. Participants are incentivized through rewards or penalties depending on their detection accuracy. On datasets such as UNSW-NB15, CSE-CIC-IDS2018, and CIC-IDS2017, MetaCIDS achieved 95–99% accuracy, outperforming classical ML models like SVM, KNN, and LightGBM.

Overall, integrating blockchain with FL provides enhanced data privacy, secure aggregation, and stronger trust mechanisms across diverse domains. With ongoing improvements in IoT device capabilities and optimization of algorithms, such architectures may become a standard paradigm for next-generation intrusion detection systems.

| Paper | Contribution | Detection Model | Blockchain Consensus Protocol | Evaluation Dataset | |

| [87] |

|

MLP | Proof of Work, Proof of Accuracy | KDDCup99 | |

| [88] |

|

FL-CGAN-LSTM | Proof of Authority | CIC-IDS2017 | |

| [89] |

|

TCGAN | Proof of Stake | ToN_IoT, LITNET-2020 | |

| [90] |

|

SVM, RF | Not Specified | Not Specified | |

| [91] |

|

AutoEncoder | PBFT | UNSW-NB15, CSE-CIC-IDS2018, CIC-IDS2017, NSL-KDD |

This section provided a structured view of privacy and trust threats in blockchain-federated IDS and mapped them to representative defense mechanisms, along with their applications in different domains. While these defense strategies offer promising directions, they also expose several fundamental challenges that remain unresolved in real-world scenarios. The next section highlights these key challenges and outlines potential avenues for future research and system design.

In this section, we discuss the challenges and potential solutions of integrating blockchain and FL in intrusion detection systems. Integrated IDS built on blockchain and FL operate without a central server. Each participant trains locally and exchanges model parameters through a blockchain ledger running on the edge network, then applies global updates on its own device. This design reduces dependence on central servers, but overall detection accuracy must be evaluated alongside blockchain-related costs, including training latency, update transmission delays, and block mining delays[24]. Further issues such as incentive mechanisms and system security also remain open. Given that research on blockchain- and federated-learning-based intrusion detection is still incomplete, we draw from existing studies and blockchain-enabled machine learning frameworks to outline the main challenges and future directions in the following subsections.

In FL and blockchain-based systems, frequent data exchanges among distributed devices may cause network congestion, especially when the number of participants increases significantly. Such congestion results in higher communication latency and potential data loss, which can become a bottleneck affecting overall system performance. The large volume of parameter transmissions and the delays introduced by multi-party exchanges are thus key factors influencing communication efficiency.

Reducing the communication overhead is a potential solution. In [92], a universal vectorization method is proposed, where each participant divides model parameters into multiple sub-vectors and independently quantizes them. The quantized sub-vectors are then aggregated at the server to form a global codeword. In subsequent rounds, participants match their sub-vectors with the codeword to generate indices, thereby reducing the amount of transmitted data.

Communication efficiency can also be improved by adjusting federated communication strategies and blockchain computation mechanisms. For instance, [93] introduces a blockchain-based FL framework for privacy-aware vehicular communication networks. The study evaluates parameters such as retransmission constraints, block size, block arrival rate, and frame size, and examines their impact on performance. Results show that as the signal-to-noise ratio increases, system latency decreases. However, channel fading in wireless communication can lead to data transmission failures, which increase blockchain fork probability and thus overall latency. Moreover, in cases of wireless loss, the latency observed by miners and vehicles is higher than that measured at the network layer. Variations in the number of vehicles and miners predictably affect learning latency, and adjusting block arrival rates can help achieve dynamic optimization. Determining the optimal arrival rate requires jointly considering the number of miners and channel propagation delay.

In [94], communication efficiency is enhanced by reducing the parameter size transmitted to the aggregation server and by optimizing transmission resource allocation. The approach employs asynchronous model updates, where participants update at different frequencies based on assigned weights that reflect their local model update frequency. This decentralized updating strategy lowers transmission overhead and avoids the synchronization delay of waiting for all users to complete training, thereby reducing overall execution time. Furthermore, the system leverages state-based digital twin technology to monitor device status and dynamically allocate communication resources according to device conditions and computing capabilities, further reducing communication time and energy consumption.

Research [95] has shown that neural networks trained with the Federated Averaging algorithm suffer a significant accuracy decline when dealing with non-independently and identically distributed (non-IID) data, primarily due to weight divergence. In federated IDS, the heterogeneous operating environments of participating devices lead to non-uniform training data, with substantial variations in distribution across devices. Such non-IID characteristics can result in model divergence during training and aggregation, particularly in horizontal FL settings.

To mitigate these challenges, [95] introduces an improved Federated Averaging approach based on a data-sharing strategy. In this method, a portion of uniformly distributed global data is provided by the aggregation server to participant devices at the initial stages of training, ensuring greater consistency across datasets. Additionally, pre-training the global model on the shared data before distributing it to participants enhances model accuracy compared to initializing with random weights.

Other strategies have also been proposed. In [96], a hierarchical clustering process measures the similarity of participants' local updates during training and iteratively merges the most similar clusters, allowing each cluster to train a dedicated model. In [97], a sparse ternary compression (STC) protocol is designed to improve accuracy on non-IID data while reducing communication overhead. By introducing sparsity and ternarizing model parameters, the protocol effectively extracts features while lowering transmission costs. Furthermore, [98] systematically categorizes solutions to non-IID issues into three groups: (i) data-based approaches, such as data sharing and augmentation, which improve training distribution; (ii) algorithm-based approaches, including participant weighting, meta-learning, and regularization strategies; and (iii) system-based approaches, such as clustering participants to build cluster-specific models.

For example, in a smart transportation deployment [99], roadside units (RSUs) at urban intersections and suburban highways collect traffic with markedly different class priors and temporal patterns, yielding non-IID local datasets. A practical avenue is to combine clustered federated learning with domain adaptation: RSUs are first grouped by similarity of update statistics, each cluster trains a dedicated model via hierarchical aggregation, and lightweight adaptation layers align feature distributions when models are transferred across clusters. This design can mitigate weight divergence, improve convergence speed, and raise detection accuracy under non-IID conditions while keeping communication overhead comparable to standard FL.

IoT is one of the primary environments for deploying IDS. While blockchain ensures data privacy and credibility, it was originally designed for powerful computing platforms rather than resource-constrained IoT devices. In blockchain- and federated-learning-based IDS, workload heterogeneity and device capability disparities significantly impact model training performance. Many IoT edge devices with limited computational resources introduce delays in block validation, storage, and consensus during training.

The study [100] evaluated two parameter update processes in blockchain–federated learning models. When the parameter server directly received and processed weight updates from deep learning servers, an additional computational overhead of 5%–15% was observed. Conversely, when updates were validated and stored on the blockchain, delays from block generation and confirmation became more pronounced. To address these issues, [101] proposed a deep reinforcement learning–based resource allocation framework. Treating blockchain transaction arrivals as a Poisson process, the system was modeled as an M/M/c queue with additional propagation delays. Optimization problems concerning device resources, block generation rates, and mining operations were formulated within a reinforcement learning framework, with Deep Q-Networks (DQN) used to derive optimal allocation strategies. Similarly, [102] introduced a digital twin network model integrating blockchain and FL into edge environments. By synchronizing with physical IoT systems, the digital twin network enabled real-time analysis and optimization of device operations, reducing resource disparities and overall system costs.

Due to computationally intensive mechanisms such as proof-of-work and encryption, blockchain deployment imposes high demands on computation, storage, and bandwidth. This creates significant pressure when applied to IoT devices. Designing lightweight blockchain platforms and consensus mechanisms tailored for IoT has thus become an important research direction. For example, [103] proposed a collaborative multi-proof-of-work consensus mechanism using a Collaborative Index (CI) framework to dynamically adjust mining difficulty, thereby reducing overhead. [104] developed a lightweight blockchain platform by improving Hyperledger Fabric and Mysitko, constructing a distributed microservices architecture with Golang and Scala to enhance concurrency and throughput. [105] introduced DV2G, a lightweight blockchain protocol employing a game-theoretic transaction model and a directed acyclic graph (DAG) structure to enable parallel transaction processing. Finally, [106] proposed the PoBT consensus protocol, which increases transaction rates in IoT systems by reducing block creation and verification costs, while employing local transaction isolation to lower storage and bandwidth requirements.

Participants providing high-quality data and models are crucial to improving system performance in FL and blockchain-based IDS. Designing appropriate incentive mechanisms ensures that such participants are sufficiently rewarded, compensating for their resource consumption and encouraging sustained contributions. Efficient incentive strategies not only improve model quality but also attract more participants, thereby expanding data coverage and enhancing detection accuracy.

Several incentive mechanisms have been proposed in the literature. In federated learning– and blockchain-based vehicular networks, [87] proposed a trust-based reward mechanism that links model accuracy with trust evaluation. When a participant's model achieves higher accuracy than others, its trust score increases; conversely, lower accuracy reduces the score. Participants can then query trust values recorded on the blockchain before verifying the received models. Models from participants whose trust value falls below a threshold are considered unreliable, even if their accuracy is high, thereby deterring malicious or inconsistent contributions.

Economic approaches have also been explored. The study [107] introduced an incentive mechanism grounded in contest theory from auction theory. By modeling repeated competitions among rational participants, the mechanism ensures protocol compliance and profit maximization. A reward policy further encourages workers to follow the protocol while receiving proportional benefits, with incentive compatibility theoretically proven.

Value-driven incentives have been proposed as well. In [108], participants contribute local data for collaborative training by initiating blockchain transactions and paying transaction fees. Fees are adjusted based on data volume—participants with larger datasets typically pay lower fees—while negotiation of total fees is supported. Rewards are granted to participants who successfully generate new blocks, aligning incentives with system goals.

Finally, privacy-aware incentive mechanisms have been investigated. The work [109] integrates privacy protection into the incentive process by delegating verification tasks to other participants. This design reduces the computation, communication, and storage burden on individual nodes, while also preventing adversaries from tracking users via IP addresses.

Although blockchain and FL enhance data privacy and security in IDS, such systems remain susceptible to adversarial and poisoning attacks.

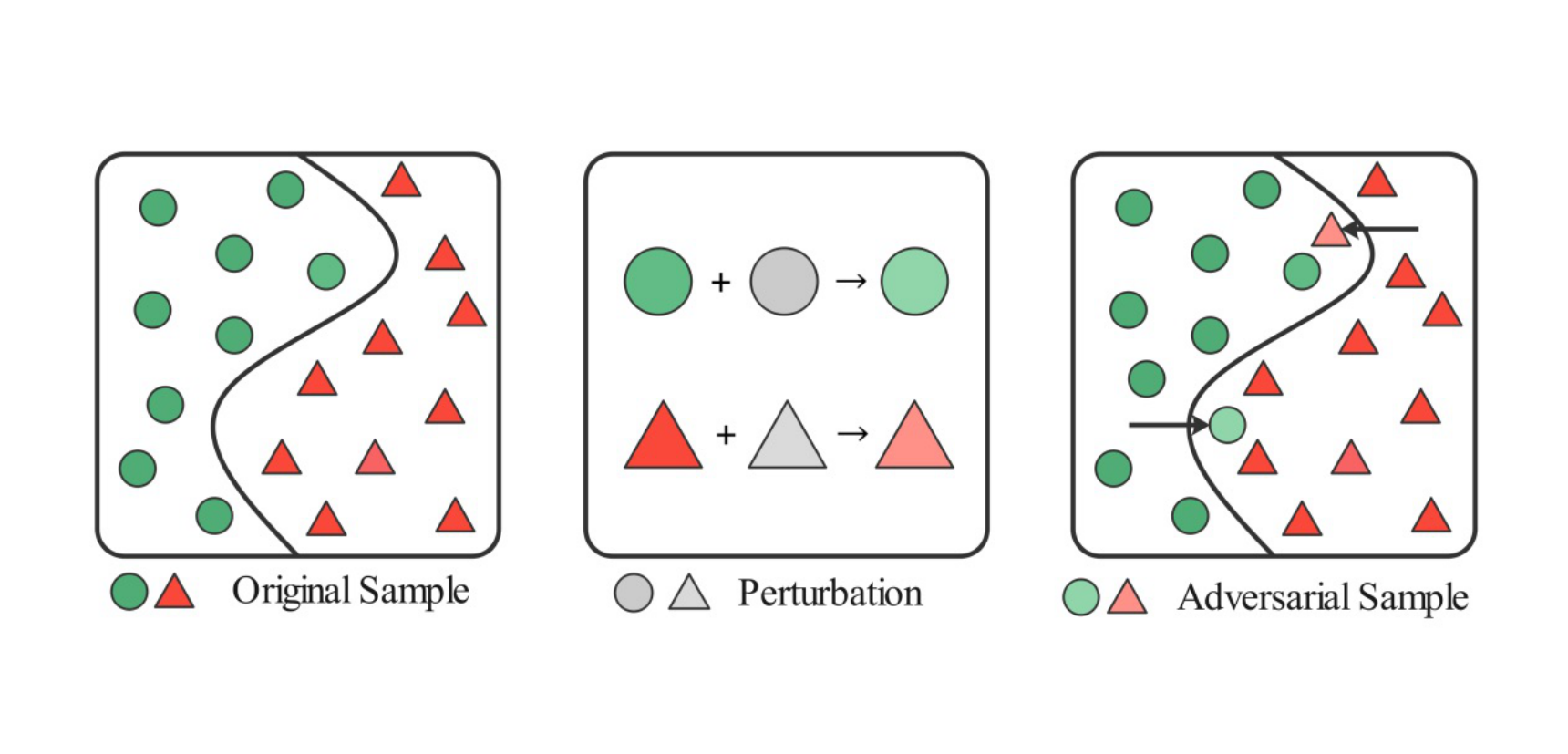

A subset of participants may behave maliciously by uploading carefully crafted poisoned parameters to the server, contaminating the global model, as illustrated in Figure 7. Models generated from these parameters typically retain good performance on most normal samples while deliberately misclassifying specific malicious traffic targeted by the attacker. To enhance the effectiveness of poisoning, [110] proposed a toxic data generation algorithm, Data Gen, based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN). In this approach, the central server shares global model parameters with the GAN discriminator, while the generator produces poisoned samples. Since direct uploads of poisoned parameters may reduce their effectiveness during model averaging, the method introduces a scaling factor to amplify gradient changes, ensuring the persistence of poisoning effects.

Adversarial attacks present another critical threat. These attacks introduce subtle perturbations into input traffic to induce misclassification, as shown in Figure 8. Most existing traffic-space adversarial attacks against IDS are white-box, assuming the attacker knows the target model's architecture and parameters. In practice, such knowledge is often unrealistic. To address this gap, [111] proposed adversarial attacks under gray-box and black-box settings by training substitute classifiers and proxy feature extractors. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) was employed to mutate traffic while reconstructing flows from metadata vectors, generating adversarial samples that preserved functionality. Similarly, [112] designed a hierarchical adversarial attack targeting IDS built on Graph Neural Networks (GNN) for IoT devices under black-box conditions. Other countermeasures, including adversarial training [113] and feature selection [114], have been widely applied to strengthen robustness.

Beyond individual studies, [115] provided a comprehensive survey of adversarial methods targeting IDS, highlighting unique challenges in traffic feature extraction compared with other domains such as image or text. While some feature-space attacks demonstrate high evasion capability, they may not translate into practical effectiveness in packet-level attacks. [116] further summarized different types, scenarios, and techniques of adversarial attacks, underscoring the need for more systematic research.

Whether new opportunities exist for designing robust defenses in blockchain- and federated-learning-based IDS remains an open question, warranting deeper exploration in future work.

This paper has surveyed existing research on IDS, FL, and blockchain, with a particular focus on how these technologies can be integrated to enhance data privacy and trust. We first analyzed data privacy and credibility issues in IDS, highlighting the vulnerabilities of centralized training approaches in edge networks with multiple participants. FL addresses these issues by enabling local training without exposing raw data, thereby reducing the risk of sensitive information leakage. At the same time, blockchain offers decentralized, immutable, and traceable parameter aggregation, providing a secure foundation for verifying, validating, and tracing multi-party contributions.

By reviewing recent studies, we have shown that the combination of FL and blockchain holds significant promise for constructing privacy-preserving and trustworthy IDS. Specifically, FL enhances collaboration among distributed participants while maintaining data confidentiality, and blockchain complements this by ensuring transparency, auditability, and resilience against single points of failure. Together, they provide new opportunities for tackling the dual challenges of privacy protection and system fairness in multi-party environments.

Despite these advances, important challenges remain. Communication efficiency, non-IID data distributions, deployment on resource-constrained IoT devices, incentive mechanisms, and system security issues such as poisoning and adversarial attacks all require further investigation. Addressing these challenges will be critical for real-world adoption and scalability.

Looking ahead, we plan to deploy IDS frameworks integrating FL and blockchain in practical edge computing environments, and to explore adaptive mechanisms to overcome the aforementioned challenges. Furthermore, we aim to extend these solutions to other domains where secure and privacy-preserving collaborative learning is essential.

Copyright © 2025 by the Author(s). Published by Institute of Central Computation and Knowledge. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

Copyright © 2025 by the Author(s). Published by Institute of Central Computation and Knowledge. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

Portico

All published articles are preserved here permanently:

https://www.portico.org/publishers/icck/